Governance

Power sector cybersecurity governance provides oversight for a utility’s cybersecurity efforts. Through governance, the utility board of directors, chief executive officer (CEO), executive leadership, and other decision makers seek to balance resource allocation, risk, and business objectives. These leaders must factor in the risk associated with cyberattacks, as well as the need to comply with national, regional, provincial, or state cybersecurity regulations. Their role is to look at cybersecurity holistically, factoring in data about current cyber vulnerabilities as well as the impact of anticipated system upgrades, increased digitalization, and system expansion.

Importance

If the upper levels of an organization do not demonstrate commitment to cybersecurity, the utility’s efforts to improve cybersecurity will enjoy little success (if any). One way to demonstrate that commitment is through allocation of resources to pay for staff time, tools, and, possibly, outside consultation. Cybersecurity governance needs to ensure those resources go where they are really needed—it is easy for organization-wide cybersecurity programs to become “lopsided,” investing too much in one area and not enough in another. Cybersecurity governance includes the work of making sure overall security efforts effectively meet the needs of the utility.

Another way for utility leadership to demonstrate commitment is by impressing on staff that everyone has a role to play in cybersecurity. They must communicate this through words as well as actions, leading by example. If staff see leadership flouting cybersecurity policies and guidelines, they will quickly realize that leadership is not serious about this topic. By “walking the walk” as well as “talking the talk,” leaders can foster a culture of cybersecurity that will help protect the utility from future cyberattacks. (For more on this topic, see the cybersecurity awareness training building block.)

Intersections With Other Building Blocks

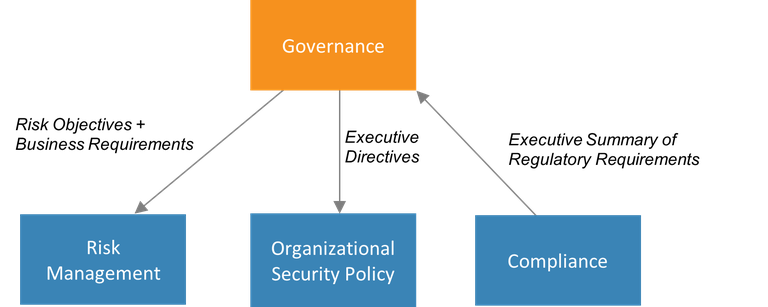

The governance building block provides input (through executive directives) that informs the development of the organizational security policy, the document that defines the utility’s cybersecurity efforts. The decision makers of the governance building block determine what cybersecurity will look like; the organizational security policy captures these decisions and presents them as actionable measures to be taken.

Governance must include compliance with all applicable regulations, so a high-level summary of regulatory requirements is provided by the compliance building block.

Governance must set the risk objectives and business requirements that define the scope of the utility’s risk management building block.

These organizational security policy, compliance, and risk management building blocks have the most interaction with governance; however, the governance building block also relies on data, reports, and other types of information from all other building blocks that might inform high-level decision-making.

Figure 1. Information passed to and from the governance building block

Process and Actions

The governance building block integrates the work of other building blocks, so there is overlap between the governance processes and actions and those in other building blocks throughout this document. Table 1 maps governance processes from the Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity from the United States National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to the building blocks that provide detail on each. In the context of the NIST framework, these processes are subcategories within the category of governance.

Table 1. NIST Governance Processes

|

From the NIST Framework |

Mapping to Building Blocks |

|

“Organizational cybersecurity policy is established and communicated.”

|

|

|

“Cybersecurity roles and responsibilities are coordinated and aligned with internal roles and external partners.”

|

Governance |

|

“Legal and regulatory requirements regarding cybersecurity, including privacy and civil liberties obligations, are understood and managed.”

|

|

|

“Governance and risk management processes address cybersecurity risks.”

|

Assigning roles and responsibilities (second row in Table 1) is uniquely a cybersecurity governance activity. The utility’s high-level decision makers must determine who will execute which parts of their cybersecurity policy and set up the necessary reporting and oversight structures needed to ensure those responsibilities are fulfilled.

DERCF assessments address governance, technical management, and physical security. DERCF can be used for free as a self-assessment tool, and users can take the assessment as an anonymous guest of the system. (In that case, the utility does not need to identify itself by name, and no data associated with the assessment is stored on the DERCF system.) NREL can also guide utilities through DERCF assessments; some utilities appreciate the participation of an outside party that can facilitate the process and communicate results to utility leadership. To learn more about DERCF, visit https://dercf.nrel.gov.

DERCF assessments address governance, technical management, and physical security. DERCF can be used for free as a self-assessment tool, and users can take the assessment as an anonymous guest of the system. (In that case, the utility does not need to identify itself by name, and no data associated with the assessment is stored on the DERCF system.) NREL can also guide utilities through DERCF assessments; some utilities appreciate the participation of an outside party that can facilitate the process and communicate results to utility leadership. To learn more about DERCF, visit https://dercf.nrel.gov.

This oversight requires a certain level of cybersecurity knowledge on the part of those decision makers. Unfortunately, not all leaders have the necessary knowledge in this area (Rothrock, Kaplan, and Van der Oord 2017). CEOs or board directors do not need to be experts in cybersecurity, but they need enough understanding to make informed decisions. Some commercial entities offer executive and board cybersecurity readiness programs (Tyler Cybersecurity n.d.). Some associations also offer guidance to boards of directors (NACD 2020) with select excerpts from those resources available online (Bew n.d.). These resources offer some ways these decision makers can acquire the requisite knowledge for executing their cybersecurity responsibilities.

For utilities that wish to benchmark the state of their cybersecurity governance, an assessment is available from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). The Distributed Energy Resource Cybersecurity Framework (DERCF) assessment tool covers three areas, one of which is governance. See box at above for details.

Essential Data

Utilities should collect or generate the data below for effective governance.

- High-level information on regulatory requirements. This is generated in the compliance building block.

- High-level information on risk, threats, and vulnerabilities affecting the utility. This is collected from cyber threat intelligence (CTI) and distilled by the risk management building block.

- Budget information. How much can the utility spend on cybersecurity? How much will compliance cost, and how much is left over to mitigate risks not covered by compliance efforts?

- Internal equipment resources. What tools and technology does the utility have for their cybersecurity efforts?

- Internal human resources. What cybersecurity expertise does the utility have in-house for the various cybersecurity activities that need to be performed? Also, how well do all the staff understand the basics of responsible, cyber-safe use of computers? (See the cybersecurity awareness training building block.)

- External resources. Where might the utility get outside help such as advice, consultation, and training? These resources could include government agencies, academics, commercial training enterprises, consultants, or not-for-profit entities.

Webinar

Watch a webinar on the cybersecurity governance building block. The audience for this session was Caribbean utilities, but many of the topics and principles discussed are universal.

Recommended Reading

Educause. “Information Security Governance.” Accessed January 4, 2021.

NIST. 2018. Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity, Version 1.1.

Additional Resources

Box. “Simplify Your IT Governance Strategy.” Accessed January 4, 2021.